Joint association of dietary pattern and socioeconomic status with the 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease

-

摘要:

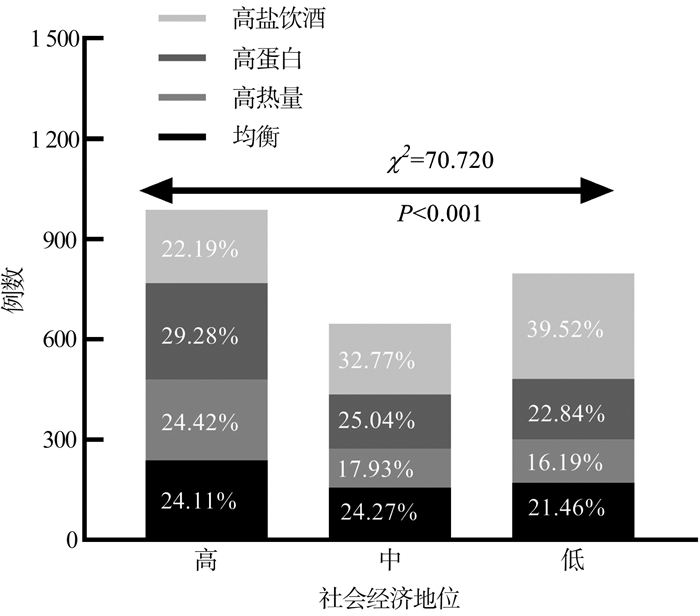

目的 探讨膳食模式与社会经济地位对心血管病10年风险的联合影响,为心血管病的防控提供参考。 方法 采用多阶段抽样方法,问卷调查2 431例北京市门头沟区居民。单因素分析探索膳食模式、社会经济地位、心血管病10年风险之间的相关关系,多因素Logistic回归分析模型分析前两者对心血管病10年风险的联合影响。 结果 北京市门头沟区常住居民心血管病10年中高风险比例为38.46%。高盐饮酒膳食模式(48.93%)和低社会经济地位(58.47%)的心血管病10年中高风险比例较高(均有P < 0.001)。调整因素后,以均衡膳食且高社会经济地位为参照,高盐饮酒膳食且低社会经济地位人群的心血管病10年中高风险比例最高(OR=6.841, 95% CI: 4.518~10.540, P < 0.001)。 结论 合理膳食需要联合考虑不同群体的社会经济地位,结合实际鼓励科学营养,以促进真实世界的心血管病防控。 Abstract:Objective To investigate the joint association of dietary pattern and socioeconomic status with the 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease, and to provide guidance for prevention and control of cardiovascular disease. Methods A questionnaire survey was conducted among 2 431 residents in the Mentougou District of Beijing, in which multi-stage sampling methods were used. Univariate analysis was performed to explore the relationships between dietary patterns, socioeconomic status, and the 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the joint association of both dietary pattern and socioeconomic status with the 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease. Results The proportion of the 10-year medium-to-high risk of cardiovascular disease among permanent residents in the Mentougou District of Beijing was 38.46%. People with high-salt-and-alcohol dietary pattern (48.93%) and low socioeconomic status (58.47%) had a higher proportion of 10-year medium-to-high risk of cardiovascular disease (all P < 0.001). After adjusting confounding factors, in comparison to people with both balanced dietary pattern and high socioeconomic status, the proportion of the 10-year medium-to-high risk of cardiovascular disease of people with both high-salt-and-alcohol dietary pattern and low socioeconomic status was highest (OR=6.841, 95% CI: 4.518~10.540, P < 0.001). Conclusions Balanced diet promotion should consider socioeconomic status. We ought to encourage a balanced diet combined with actual conditions of different socioeconomic status to prevent and control cardiovascular disease in the real world. -

表 1 17个食物组主成分分析的成分载荷结果

Table 1. Component loading results of principal component analysis for 17 food groups

食物 均衡DP 高热量DP 高蛋白DP 高盐饮酒DP 谷类 0.66 -0.11 0.04 0.08 薯类 0.26 0.06 0.40 0.10 新鲜蔬菜 0.60 0.04 0.13 -0.24 水果 0.54 0.21 0.11 -0.43 酱腌蔬菜 0.39 0.11 -0.09 0.45 畜禽肉类 0.52 0.10 0.25 0.02 水产品 0.02 0.12 0.73 -0.04 蛋类 0.06 0.04 0.76 0.00 奶类 0.12 0.09 0.34 -0.49 大豆及其制品 0.06 0.17 0.05 -0.17 坚果 0.20 0.36 0.17 -0.18 油脂 0.45 0.07 -0.01 0.08 甜点 -0.14 0.74 0.07 0.02 膨化食品 0.04 0.80 0.07 -0.03 油炸面食 0.15 0.67 -0.01 0.07 盐 -0.01 0.11 0.14 0.63 酒精 0.04 -0.05 0.05 0.34 表 2 膳食模式、社会经济地位的分布特征比较[n(%)]

Table 2. Comparison of the distribution characteristics of dietary patterns and socioeconomic status [n(%)]

特征 膳食模式 社会经济地位 均衡

(n=566)高热量

(n=486)高蛋白

(n=633)高盐饮酒

(n=746)χ2/F值 高

(n=987)中

(n=647)低

(n=797)χ2/F值 性别 129.721a 17.854a 男 313(29.61) 134(12.68) 217(20.53) 393(37.18) 466(44.09) 292(27.63) 299(28.29) 女 253(18.41) 352(25.62) 416(30.28) 353(25.69) 521(37.92) 355(25.84) 498(36.24) 年龄(x±s, 岁) 47.12±13.86 46.07±14.49 50.34±13.94 50.23±12.66 14.717a 40.53±12.56 51.03±12.56 56.94±10.05 444.020a 现居住地 37.874a 546.239a 城市 370(23.30) 326(20.53) 463(29.16) 429(27.02) 877(55.23) 425(26.76) 286(18.01) 农村 196(23.25) 160(18.98) 170(20.17) 317(37.60) 110(13.05) 222(26.33) 511(60.62) 婚姻状况 18.231b 150.325a 已婚 480(23.23) 405(19.60) 537(25.99) 644(31.17) 791(38.29) 563(27.25) 712(34.36) 未婚 62(29.25) 53(25.00) 45(21.23) 52(24.53) 161(75.94) 36(16.98) 15(7.08) 丧偶/离异 18(16.07) 16(14.29) 35(31.25) 43(38.39) 18(16.07) 36(32.14) 58(51.79) 是否吸烟 87.548a 8.884 目前吸烟 170(28.52) 84(14.09) 94(15.77) 248(41.61) 213(35.74) 171(28.69) 212(35.57) 已戒烟 8(25.00) 4(12.50) 10(0.33) 10(31.25) 12(37.50) 7(21.88) 13(40.62) 从未吸烟 388(21.52) 398(22.07) 529(29.34) 488(27.07) 762(42.26) 469(26.01) 572(31.72) 体力活动 22.322b 15.865b 低 63(31.34) 35(17.34) 36(17.91) 67(33.33) 103(51.24) 52(25.87) 46(22.89) 中 55(16.72) 79(24.01) 87(26.44) 108(32.83) 144(43.77) 83(25.23) 102(31.00) 高 447(23.65) 369(19.52) 509(26.93) 565(29.89) 733(38.78) 510(26.98) 647(34.23) BMI (kg/m2) 25.94±4.10 24.74±3.55 25.05±3.92 25.43±3.66 10.105a 24.68±3.93 25.73±3.99 25.78±3.46 23.780a 注:a表示P < 0.001;b表示P < 0.01。 表 3 Logistic回归变量赋值表

Table 3. Logistic regression variable assignment table

变量 赋值情况 CVD风险 低危=0,中高危=1 DP 均衡DP=1,高热量DP=2,高蛋白DP=3,高盐饮酒DP=4 SES 高SES=1,中SES=2,低SES=3 DP与SES 均衡DP与高SES=1,均衡DP与中SES=2,均衡DP与低SES=3,高热量DP与高SES=4,高热量DP与中SES=5,高热量DP与低SES=6,高蛋白DP与高SES=7,高蛋白DP与中SES=8,高蛋白DP与低SES=9,高盐饮酒DP与高SES=10,高盐饮酒DP与中SES=11,高盐饮酒DP与低SES=12 婚姻状况 已婚=1,未婚=2,丧偶或离异=3 BMI(kg/m2) 连续型变量 体力活动水平 高=1,中=2,低=3 注:因变量CVD风险计算时已考虑性别、年龄、城市或农村、腰围、TC、HDL-C、当前收缩压水平、是否服用降压药、是否患有糖尿病、现在是否吸烟,是否有心血管病家族史等,故上述因素不在回归分析里再做调整。 表 4 膳食模式、社会经济地位与心血管病10年风险的Logistic回归结果

Table 4. Logistic regression results of dietary pattern, socioeconomic status and 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease

变量 模型1 模型2 模型3 模型4 OR(95% CI)值 OR(95% CI)值 OR(95% CI)值 变量 OR值(95% CI)值 膳食模式 膳食模式*社会经济地位 均衡 1.000 1.000 均衡*高 1.000 高热量 0.673(0.509~0.888)b 0.699(0.522~0.933)a 均衡*中 3.129(1.939~5.100)c 高蛋白 0.900(0.700~1.157) 0.945(0.727~1.230) 均衡*低 6.614(4.152~10.708)c 高盐饮酒 1.540(1.217~1.951)c 1.337(1.045~1.711)a 高热量*高 0.719(0.420~1.217) 社会经济地位 高热量*中 1.800(1.038~3.111)a 高 1.000 1.000 高热量*低 5.215(3.173~8.689)c 中 2.586(2.050~3.268)c 2.478(1.961~3.137)c 高蛋白*高 1.190(0.749~1.902) 低 4.936(3.955~6.180)c 4.640(3.701~5.823)c 高蛋白*中 3.355(2.092~5.441)c 高蛋白*低 4.537(2.863~7.289)c 高盐饮酒*高 2.113(1.338~3.371)b 高盐饮酒*中 3.808(2.449~6.006)c 高盐饮酒*低 6.841(4.518~10.540)c 注:a表示P < 0.05;b表示P < 0.01;c表示P < 0.001。模型1表示CVD风险~DT;模型2表示CVD风险~SES;模型3表示CVD风险~(DP+SES);模型4表示CVD风险~(DP*SES);所有模型均调整BMI、婚姻状况、体力活动水平。 -

[1] 胡盛寿, 高润霖, 刘力生, 等. 《中国心血管病报告2018》概要[J]. 中国循环杂志, 2019, 34(3): 209-220. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2019.03.001.Hu SS, Gao RL, Liu LS, et al. Summary of the 2018 Report on Cardiovascular Diseases in China[J]. Chin Circul J, 2019, 34(3): 209-220. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2019.03.001. [2] 吕淑荣, 俞浩, 苏健, 等. 膳食模式与心脑血管病死亡风险关系的巢式病例-对照研究[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2016, 50(10): 912-913. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2016.10.014.Lv SR, Yu H, Su J, et al. Dietary patterns and the risk of cardiovascular disease mortality: a nested case-control study[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2016, 50(10): 912-913. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2016.10.014. [3] Ochoa-Avilés A, Verstraeten R, Lachat C, et al. Dietary intake practices associated with cardiovascular risk in urban and rural Ecuadorian adolescents: a cross-sectional study[J]. BMC Public Health, 2014, 14(9): 939. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-939. [4] Li F, Hou LN, Chen W, et al. Associations of dietary patterns with the risk of all-cause, CVD and stroke mortality: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies[J]. Br J Nutr, 2015, 113(1): 16-24. DOI: 10.1017/S000711451400289X. [5] Atkins JL, Whincup PH, Morris RW, et al. Dietary patterns and the risk of CVD and all-cause mortality in older British men[J]. Br J Nutr, 2016, 116(7): 1246-1255. DOI: 10.1017/S0007114516003147. [6] Bonaccio M, Di Castelnuovo A, Pounis G, et al. High adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with cardiovascular protection in higher but not in lower socioeconomic groups: prospective findings from the Moli-sani study[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2017, 46(5): 1478-1487. DOI: 10.1093/ije/dyx145. [7] Miyaki K, Song Y, Taneichi S, et al. Socioeconomic status is significantly associated with dietary salt intakes and blood pressure in Japanese workers (J-HOPE Study)[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2013, 10(3): 980-993. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph10030980. [8] 中国心血管病风险评估和管理指南编写联合委员会. 中国心血管病风险评估和管理指南[J]. 中国循环杂志, 2019, 34(1): 4-28. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2019.01.002.The Joint Task Force Assessme. Guideline on the Assessment and Management of Cardiovascular Risk in China[J]. Chin Circul J, 2019, 34(1): 4-28. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2019.01.002. [9] Yang X, Li J, Hu D, et al. Predicting the 10-year risks of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in Chinese population: the China-PAR project (prediction for ASCVD risk in China)[J]. Circulation, 2016, 134(19): 1430-1440. DOI: 10.1161/circulationaha.116.022367. [10] 刘晓芬, 赵清水, 何莹, 等. 2017年北京市房山区35岁及以上居民心血管病相关危险因素分布及风险评估[J]. 首都公共卫生, 2019, 13(3): 130-133. DOI: 10.16760/j.cnki.sdggws.2019.03.004.Liu XF, Zhao QS, He Y, et al. Distribution of risk factors and overall risk assessment of cardiovascular disease among residents over 35 years of age in Fangshan of Beijing, 2017[J]. Capital Journal of Public Health, 2019, 13(3): 130-133. DOI: 10.16760/j.cnki.sdggws.2019.03.004. [11] 但丽琼, 高彬, 唐莉, 等. 湖北赤壁市心血管病高危人群筛查及危险因素[J]. 公共卫生与预防医学, 2018, 29(6): 110-113. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-2483.2018.06.028.Dan LQ, Gao B, Tang L, et al. Screening and risk factors of high risk population of cardiovascular disease in Chibi, Hubei Province[J]. Pub Health and Prev Med, 2018, 29(6): 110-113. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-2483.2018.06.028. [12] 侯刚. 河南省心血管病高危人群筛查及主要危险因素研究[D]. 郑州: 郑州大学, 2018.Hou G. Study of screening and major risk factors associated with high risk groups for cardiovascular disease in Henan Province[D]. Zhengzhou: Zhengzhou University, 2018. [13] 冯伟, 王如庆, 邬家静. 两种方法预测≥35岁居民心血管病发病风险的结果比较[J]. 现代实用医学, 2017, 29(8): 1007-1009. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-0800.2017.08.016.Feng W, Wang RQ, Wu JJ. Comparison of the results of two methods for predicting the risk of cardiovascular disease among residents ≥35 years of age[J]. Mod Pract Med, 2017, 29(8): 1007-1009. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-0800.2017.08.016. [14] Yang XL, Chen JC, Li JX, et al. Risk stratification of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in Chinese adults[J]. Chronic Dis Transl Med, 2016, 2(2): 102-109. DOI: 10.1016/j.cdtm.2016.10.001. [15] Wang X, Zhang T, Wu J, et al. The association between socioeconomic status, smoking, and chronic disease in Inner Mongolia in Northern China[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019, 16(2). DOI: 10.3390/ijerph16020169. [16] 樊萌语, 吕筠, 何平平. 国际体力活动问卷中体力活动水平的计算方法[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2014, 35(8): 961-964. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2014.08.019.Fan MY, Lv Y, He PP. Chinese guidelines for data processing and analysis concerning the international physical activity questionnaire[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2014, 35(8): 961-964. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2014.08.019. [17] Frazier-Wood AC, Kim J, Davis JS, et al. In cross-sectional observations, dietary quality is not associated with CVD risk in women; in men the positive association is accounted for by BMI[J]. Br J Nutr, 2015, 113(8): 1244-1253. DOI: 10.1017/S0007114515000185. [18] Wong CW, Kwok CS, Narain A, 等. 婚姻状况与心血管病风险的关系: 系统评价和荟萃分析[J]. 中华高血压杂志, 2018, 26(9): 899. DOI: 10.16439/j.cnki.1673-7245.2018.09.033.Wong CW, Kwok CS, Narain A, et al. Marital status and risk of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Chin J Hypertens, 2018, 26(9): 899. DOI: 10.16439/j.cnki.1673-7245.2018.09.033. [19] 程水华, 朱建军, 王文, 等. 汇集队列风险方程与China-PAR模型在体检人群ASCVD风险预测中的应用[J]. 中国循证心血管医学杂志, 2020, 12(2): 131-134. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4055.2020.02.02.Cheng SH, Zhu JJ, Wang W, et al. Application of pooled cohort risk equations and China-PAR model in ASCVD risk prediction among people with physical examination[J]. Chin J Evid Based Cardiovasc Med, 2020, 12(2): 131-134. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4055.2020.02.02. [20] 中国心血管健康与疾病报告编写组. 中国心血管健康与疾病报告2019概要[J]. 中国循环杂志, 2020, 35(9): 833-854. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2020.09.001.The Writing Committee Of China. Report on Cardiovascular Health and Diseases in China 2019: an Updated Summary[J]. Chin Circul J, 2020, 35(9): 833-854. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2020.09.001. [21] Jones NRV, Forouhi NG, Khaw KT, et al. Accordance to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet pattern and cardiovascular disease in a British, population-based cohort[J]. Eur J Epidemiol, 2018, 33(2): 235-244. DOI: 10.1007/s10654-017-0354-8. [22] Strazzullo P, D'Elia L, Kandala NB, et al. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies[J]. BMJ, 2009, 339: b4567. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.b4567. [23] Millwood IY, Walters RG, Mei XW, et al. Conventional and genetic evidence on alcohol and vascular disease aetiology: a prospective study of 500 000 men and women in China[J]. Lancet, 2019, 393(10183): 1831-1842. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31772-0. [24] Becerra-Tomás N, Paz-Graniel I, W C Kendall C, et al. Nut consumption and incidence of cardiovascular diseases and cardiovascular disease mortality: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies[J]. Nutr Rev, 2019, 77(10): 691-709. DOI: 10.1093/nutrit/nuz042. [25] Stefano M, Maria IP, Claudia SG, et al. Legume consumption and CVD risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Public Health Nutr, 2017, 20(2): 245-254. DOI: 10.1017/S1368980016002299. [26] Quispe R, Benziger CP, Bazo-Alvarez JC, et al. The relationship between socioeconomic status and CV risk factors: the CRONICAS cohort study of peruvian adults[J]. Glob Heart, 2016, 11(1): 121-130. DOI: 10.1016/j.gheart.2015.12.005. [27] 王馨, 申洋, 王增武, 等. 职业人群理想心血管健康状况及其与社会经济地位的关联研究[J]. 中国循环杂志, 2018, 33(5): 446-451. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2018.05.007.Wang X, Shen Y, Wang ZW, et al. Prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health status and its association with socioeconomic status in Chinese enterprise employees[J]. Chinese Circulation Journal, 2018, 33(5): 446-451. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2018.05.007. [28] 茅群霞. 心率及社会经济地位与我国成年人心血管病相关性研究[D]. 北京: 北京协和医学院, 2010.Mao QX. Hearthrate, socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease in Chinese adults[D]. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College, 2010. [29] Ali MK, Bhaskarapillai B, Shivashankar R, et al. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular risk in urban South Asia: The CARRS Study[J]. Eur J Prev Cardiol, 2016, 23(4): 408-419. DOI: 10.1177/2047487315580891. [30] Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Chrysohoou C, et al. Dietary habits mediate the relationship between socio-economic status and CVD factors among healthy adults: the ATTICA study[J]. Public Health Nutr, 2008, 11(12): 1342-1349. DOI: 10.1017/S1368980008002978. [31] Méjean C, Droomers M, van der Schouw YT, et al. The contribution of diet and lifestyle to socioeconomic inequalities in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality[J]. Int J Cardiol, 2013, 168(6): 5190-5195. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.07.188. -

下载:

下载: